“If I’d tried for them dinky singles, I could’ve batted around six hundred.” – Babe Ruth

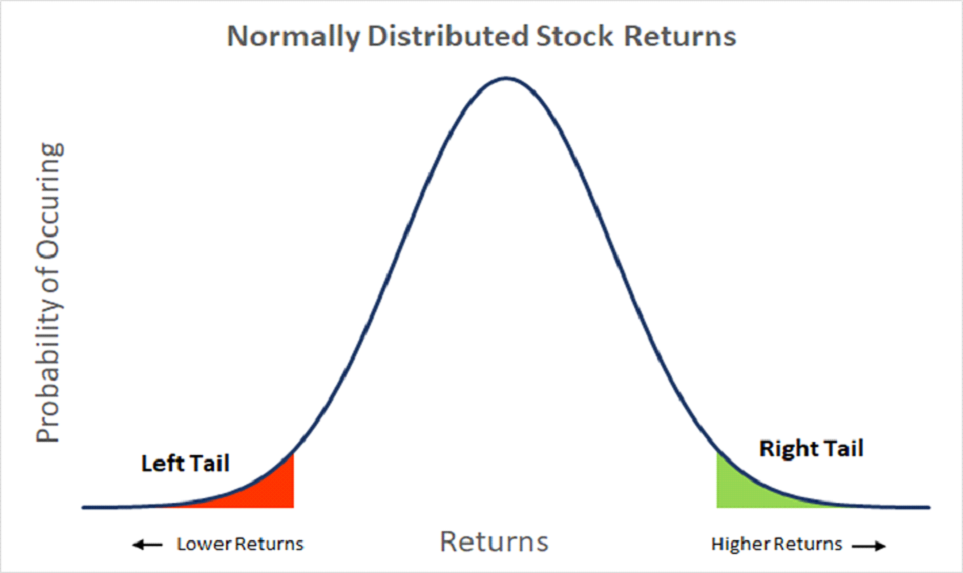

Babe Ruth is considered one of the greatest baseball players of all time. He hit 714 home runs, a league record at the time. Over his career, he collected 2,873 base hits. He was a seven-time World Series champion, and he made baseball’s “All Century” team. However, for many years, Babe Ruth was also known as the “King of Strikeouts.” He led the American League in strikeouts five times and accumulated 1,330 of them in his career. However, despite his large number of strikeouts, he was one of baseball’s greatest hitters, establishing many MLB batting records, including career home runs. Babe Ruth accepted his failures because he knew his successes would more than make up for them. His approach and mindset illustrate one of the most important concepts in portfolio management and investing: expected value or mathematical expectancy. Celebrated hedge fund tycoon George Soros, the man who broke the Bank of England after making a profit of $1 billion by shorting the British pound, once summed up the same concept by stating: “It’s not whether you’re right or wrong that’s important, but how much money you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong.” This is also called the Babe Ruth effect. In other words, it is not the frequency of winning that matters but the frequency times the magnitude of the payoff.

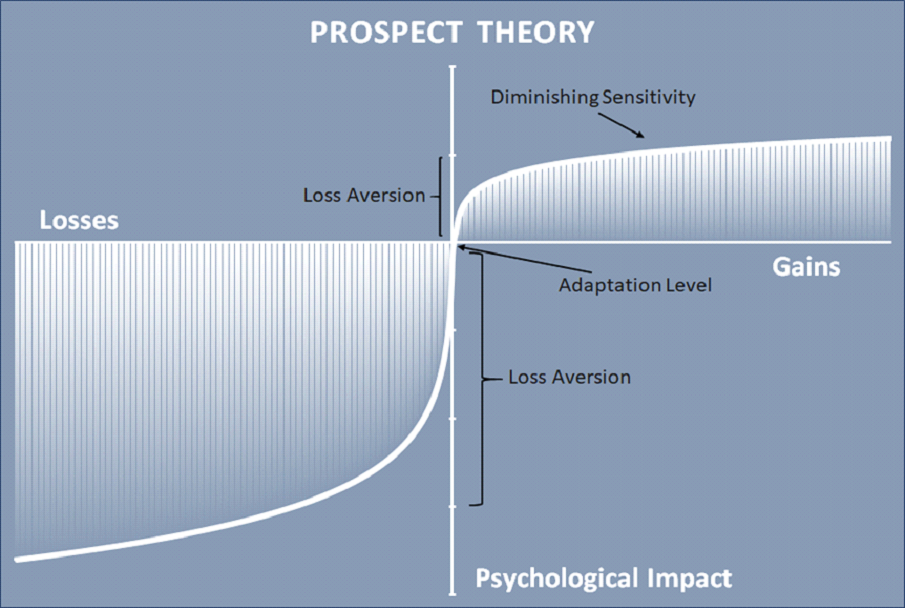

However, many people are wired to avoid losses when making risky choices when the probability of different outcomes is unknown. In fact, investors are known to perceive losses on their investments as greater than they actually are. This is outlined in prospect theory, which was formulated in 1979 by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Investors naturally prefer to be right more frequently than they are wrong. However, this mindset causes investors to overlook the key concept that the frequency of correctness does not matter as much as the magnitude of correctness.

The understanding of frequency versus magnitude, or in other words, the understanding of winning a few big payoffs while taking small, frequent losses, goes against investors’ intuitions. This investor bias of prioritizing correctness over payoff magnitude goes to show the importance of focusing on expected value when making investment decisions.

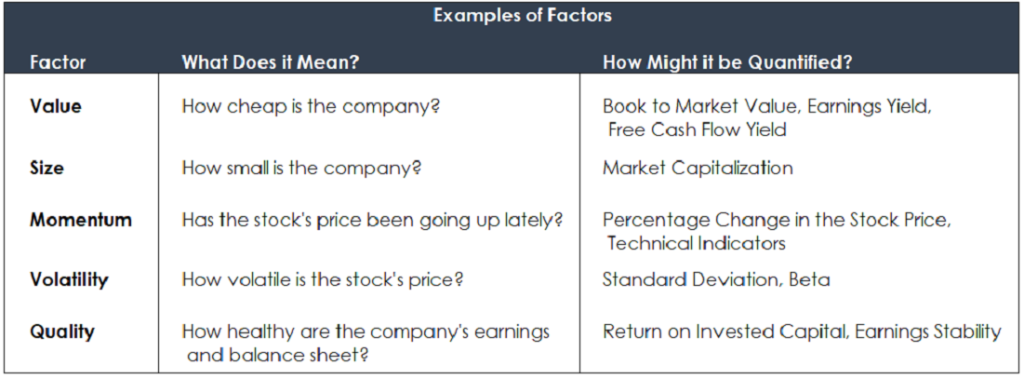

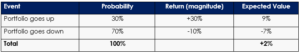

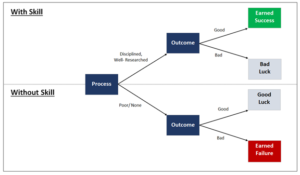

For example, take a look at this hypothetical portfolio below:

As you can see, even though the probability of the portfolio going up is less than the probability of the portfolio going down, the magnitude of portfolio return when the portfolio goes up offsets the higher probability of loss when the portfolio goes down. Therefore, the expected value, how much your portfolio is expected to gain or lose on average, is positive.

To sum it all up, investors do not necessarily need to be exactly like Babe Ruth or George Soros to have long-term success in these types of probabilistic exercises. However, it is essential that investors understand expected values, risk management, and perhaps, most importantly, themselves and their own emotional tendencies if they wish to achieve success with their investments. Keep in mind, just because something has a lower probability, it doesn’t mean that it’s not worth betting on.

The views expressed represent the opinion of Passage Global Capital Management, LLC. The views are subject to change and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This material is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute as investment advice and is not intended as an endorsement of any specific investment. Stated information is derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources that have not been independently verified for accuracy or completeness. While Passage Global Capital Management, LLC believes the information to be accurate and reliable, we do not claim or have responsibility for its completeness, accuracy, or reliability. Statements of future expectations, estimates, projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information and Passage Global Capital Management, LLC’s views as of the time of these statements. Accordingly, such statements are inherently speculative as they are based on assumption that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Actual results, performance or events may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements.

Computational power has roughly doubled every two years since the 1970s

Computational power has roughly doubled every two years since the 1970s