“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t, pays it.”

– Albert Einstein

The most important concept pertinent to investing is the arithmetic of compounding. The math is not immediately intuitive, but the effects, both positive and negative, have momentous impacts on portfolio returns. Investors who understand the drivers of compounding are best positioned for long-term success. Alternately, nearsighted investors who ignore the significance of compounding may struggle to reach their desired objectives.

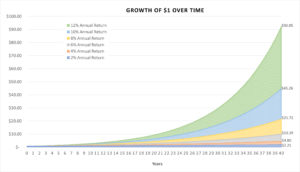

Much has already been written about the importance of long-term investing, but the specific reason why it is essential to retain a long-term mindset often goes overlooked. It is easy to believe that stock market riches lie in huge overnight gains, especially after the GameStop incident earlier this year. The firestorm of media coverage surrounding these events can easily induce investors to subconsciously overestimate the frequency of such occurrences. However, in reality, patient investors have a much better chance of reaching “riches” in the stock market due to the exponential growth of compounding over time. Suppose an investment returns 10% per year. After ten years, each dollar invested would be worth $2.59. After twenty years, each dollar would be $6.72. After 30 years, each dollar would be $17.45. It is evident that the growth is not linear; it is exponential. Each incremental increase in portfolio value leads to larger changes in the future.

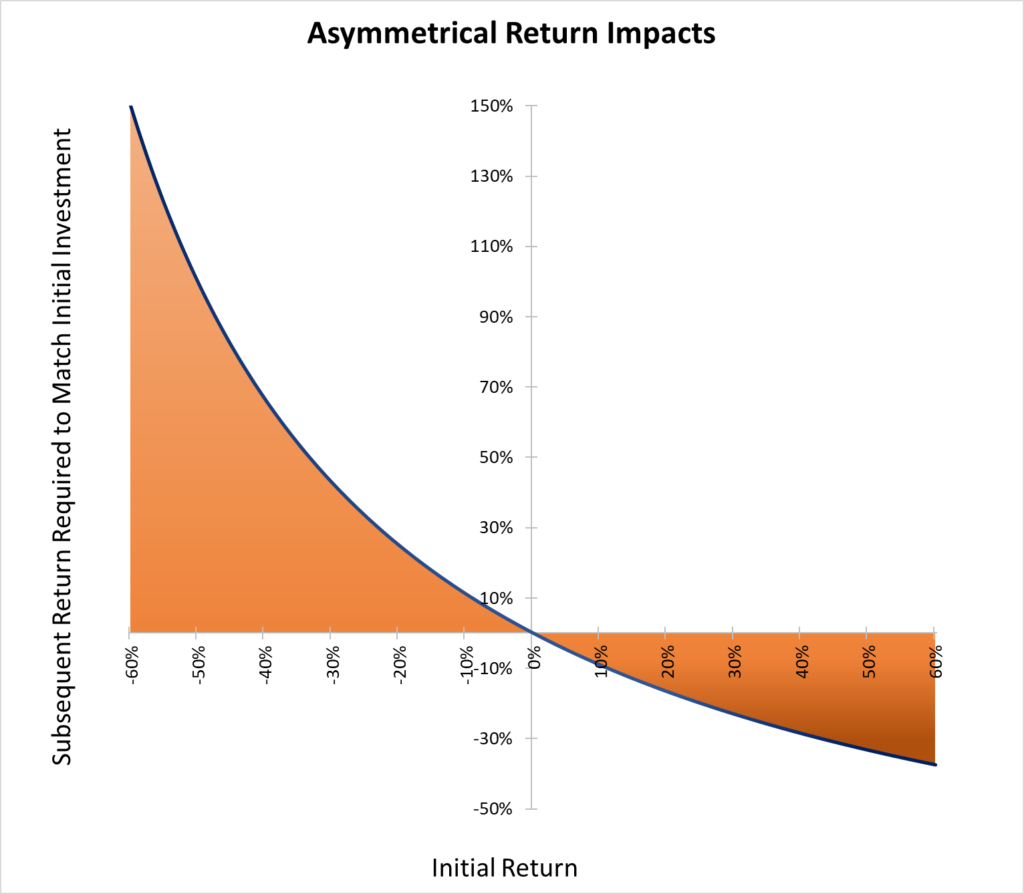

Despite the benefits, compounding can also have tremendously adverse consequences for investors. The effects of positive and negative returns are asymmetrical, meaning negative returns actually have a larger impact on the portfolio in dollar terms than positive returns of the same percentage. To illustrate, consider an investment of $1 million. After undergoing a rough period in the market, the value of the investment is now $500,000, for a 50% loss. However, we cannot simply rely on a 50% gain to bring the investment back to $1 million. Now that the value is only $500,000, we must double our money for a 100% gain in order to get back to where we started.

The question then becomes how investors can use compounding to their advantage rather than fall prey to unfavorable outcomes. Risk management and investor temperament are crucial. Risk is unavoidable. However, the amount of risk that is being taken must be carefully measured and monitored to ensure that it is not out of line with what the investor can tolerate. Investment professionals typically measure risk by volatility, or standard deviation. High volatility implies a magnitude of returns higher than historical tendencies would estimate. Note that magnitude says nothing about direction. It is not necessary that volatility will ultimately result in harm to an investors’ portfolio since volatility does not imply permanent loss; it only implies wide swings in value. However, when investor behavior is involved, volatility can easily result in permanent loss. This is especially true if it turns out that the portfolio risk was not properly managed or was more than the investor’s risk tolerance could allow for. The investor may panic and sell, foregoing potential high volatility gains in the recovery. Over the long-term the impact of these mistakes can be devastating even though the true impact might not be clear on the surface. The reason: compounding. The investor is missing out on the largest gains of the recovery, and when they do eventually get back in, their portfolio is starting from a lower value. Investors would be wise to follow Charlie Munger’s first rule of compounding: “Never interrupt it unnecessarily.”

Of course, the caveat to Munger’s quote is the word, “unnecessarily.” Just as investors can fall into the trap of panic selling, they may be influenced by the disposition effect. The disposition effect is a behavioral anomaly referring to investors’ natural tendencies to sell assets that have risen in price (thus locking in gains) and hold onto assets that have fallen (thus avoiding the aforementioned permanent loss). Each situation is different, and there is no clear answer on how to act. To maximize the probability of success over the long-term, it is vital for investors to have an investment process that they follow with discipline. This can help minimize the influence of emotions and allow their investments to compound over time.

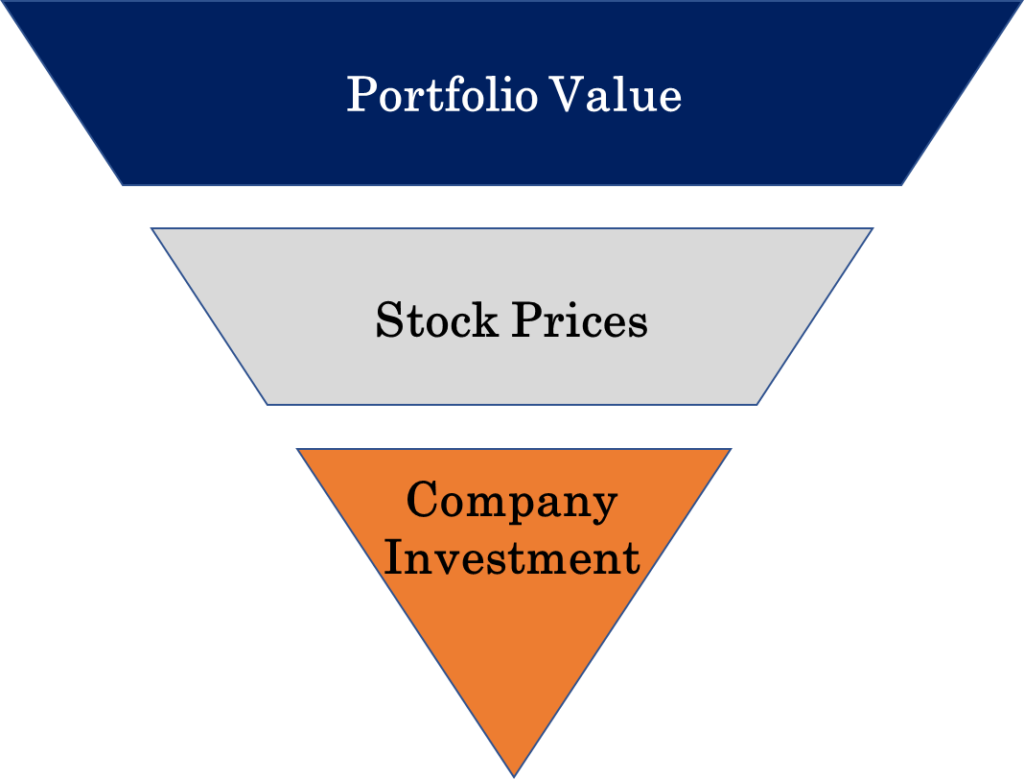

Compounding, as it relates to investing, occurs at multiple levels. At the highest level is the compounding of the portfolio value. This is not only related to the individual performance of the underlying securities but also how the portfolio is constructed and how drawdowns are managed (drawdowns are the losses of the portfolio from peak to valley). Diversification is imperative for reducing portfolio risk. The bellwether for diversification is the balanced portfolio consisting of stocks and bonds. Historically, the correlation between stocks and bonds has been low. This has allowed the two asset classes to perform particularly well together and lessen the volatility as compared to an all-stock portfolio. There are also more complex strategies that can be used. Hedge funds are well known for their focus on risk mitigation. Many hedge funds employ long-short strategies where they bet on certain stocks and against others. The offsetting positions, they hope, will minimize the systematic (market) risk and allow the fund to grow steadily despite market conditions (depending on the specific strategy; there are many variations of the long-short portfolio). These are only a few examples, but there are numerous types of strategies with the same aim: achieving steady returns and avoiding significant drawdowns to maximize portfolio growth over time.

The second level of compounding occurs at the individual stock price level. Famed mutual fund manager Peter Lynch popularized the term “tenbagger” to describe stocks that increase ten-fold over the initial buy price. Many investors focus specifically on seeking out these kinds of stocks. Needless to say, tenbaggers are rarities, but not every stock needs to be a tenbagger for an investment to be considered a success. Some investors may even find success through trading stocks over short time horizons (e.g., weeks, days, seconds, etc.). Renaissance Technologies’ Medallion Fund is the quintessential example. The quantitative hedge fund (which is now closed to the public) is believed to have achieved an astonishing average annual return of 66% gross of fees from 1988 to 2018 according to author Gregory Zuckerman. This was done by consistently generating small gains and using a fair amount of leverage in a large portfolio of securities. Due to the mathematics of compounding, these small gains do not simply add up over time; they multiply, which can result in staggering numbers.

Disclaimer

The views expressed represent the opinion of Passage Global Capital Management, LLC. The views are subject to change and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This material is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice and is not intended as an endorsement of any specific investment. Stated information is derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources that have not been independently verified for accuracy or completeness. While Passage Global Capital Management, LLC believes the information to be accurate and reliable, we do not claim or have responsibility for its completeness, accuracy, or reliability. Statements of future expectations, estimates, projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information and Passage Global Capital Management, LLC’s views as of the time of these statements. Accordingly, such statements are inherently speculative as they are based on assumptions that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Actual results, performance, or events may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements.