In 1738 the Swiss mathematician Daniel Bernoulli wrote a famous essay in which he introduced utility theory about the psychological value of money. Bernoulli’s model assumed that the utility that was assigned to a given state of wealth did not vary with the decision maker’s initial state of wealth.

Later in the 20th century, two psychologists, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize winner in Economic Sciences), concluded in their 1979 seminal paper, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” that people make decisions based on changes of wealth as opposed to states of wealth. In an investing context, when looking at brokerage account statements, people psychologically place greater emphasis on the gains and losses for the period than the ending balance of their portfolio.

As an example, consider two investors: John and Mary. John’s wealth has gone up from $1 million to $1.5 million, and Mary’s wealth has gone down from $4 million to $3.5 million. Who is happier? Obviously, John is happier than Mary. Who is better off financially? Mary is better off given her larger amount of wealth.

Bernoulli’s model focuses on the utility of wealth, which essentially measures who is better off financially, but ignores the all-important role of the reference point, the earlier state relative to which gains and losses are evaluated. While Bernoulli’s utility theory requires one to know only the state of wealth to determine its utility, prospect theory also requires knowing the reference state.

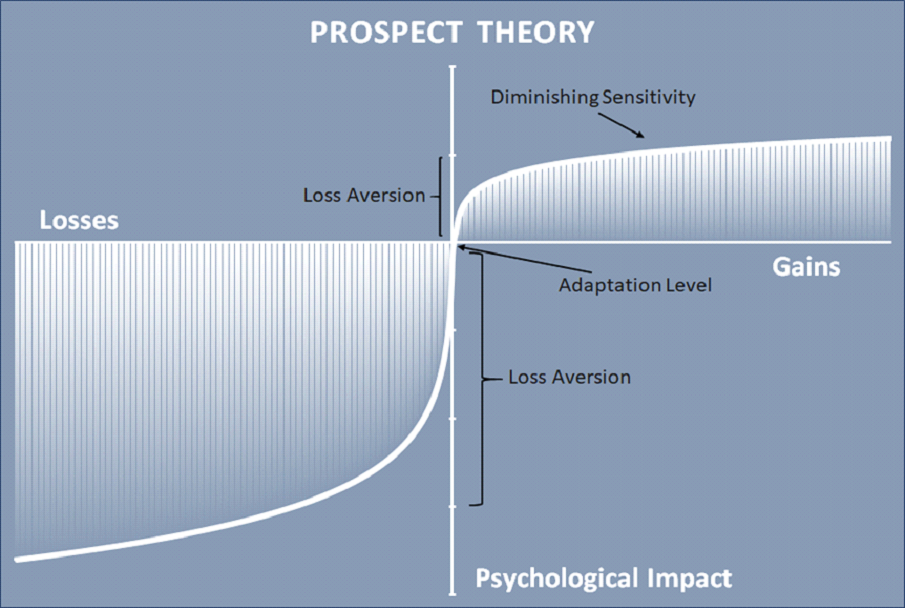

Prospect theory has three cognitive principles that govern the value of outcomes:  Adaptation level: this is the evaluation relative to a neutral reference point. Financial outcomes that are above the reference points are gains. Below the reference points are losses.

Adaptation level: this is the evaluation relative to a neutral reference point. Financial outcomes that are above the reference points are gains. Below the reference points are losses.

Diminishing sensitivity: the subjective difference between $900 and $1000 is much smaller than the difference between $100 and $200.

Diminishing sensitivity: the subjective difference between $900 and $1000 is much smaller than the difference between $100 and $200.

Loss aversion: when people think in terms of the final state of wealth, they tend to be much less risk-averse. However, when people think in terms of gains and losses, they tend to be more risk-averse, because losses loom much larger than gains.

Loss aversion: when people think in terms of the final state of wealth, they tend to be much less risk-averse. However, when people think in terms of gains and losses, they tend to be more risk-averse, because losses loom much larger than gains.

To demonstrate a loss aversion example, consider a flip of a coin. If it lands heads, you gain $150, but if it is tails, you lose $100. Is this gamble attractive enough for you to play? This will require you to evaluate the psychological benefit of gain versus the psychological cost of loss. Most people tend to avoid this gamble for fear of potentially losing $100 versus the hope of gaining $150 despite the fact that the expected value of the gamble is positive. This helps explain risk aversion in the sense that the disutility of losing $1 is higher than the utility of winning $1.

The views expressed represent the opinion of Passage Global Capital Management, LLC. The views are subject to change and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This material is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute as investment advice and is not intended as an endorsement of any specific investment. Stated information is derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources that have not been independently verified for accuracy or completeness. While Passage Global Capital Management, LLC believes the information to be accurate and reliable, we do not claim or have responsibility for its completeness, accuracy, or reliability. Statements of future expectations, estimates, projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information and Passage Global Capital Management, LLC’s views as of the time of these statements. Accordingly, such statements are inherently speculative as they are based on assumption that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Actual results, performance or events may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements.