Paul DePodesta, a former baseball executive and one of the protagonists in Michael Lewis’s Moneyball, shares a story about playing blackjack in Las Vegas when a guy to his right, sitting on 17, ask for a hit. Everyone at the table is surprised and even the dealer asks if he is sure. The player nods yes, and the dealer produces a four and says, “Nice hit.” But was it really a smart play? Of course not (unless you work for the casino). The probability of going bust with a 17 is 69%. The player was simply lucky. If he continued to hit on every 17 he had been dealt, he would lose most of the time.

On the other side of the coin, sometimes decisions that may have seemed sound at the time they were made result in unfavorable outcomes. Consider an example highlighted by poker champion Annie Duke in her book Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts. It involves one of the most infamous play calls in the history of football: the decision by Seattle Seahawks coach Pete Carroll to throw the ball at the one-yard line rather than hand the ball off to star running back Marshawn Lynch to end Super Bowl XLIX. The pass was intercepted in the end-zone and the decision cost the Seahawks not only the game, but the NFL championship. Carroll was widely ridiculed for the decision but perhaps the hate is undeserved considering that an incomplete pass would have stopped the clock giving the Seahawks some much needed time to score. Additionally, according to Duke, only 2% of passes from the 1-yard line within the previous 15 years had been intercepted. In all likelihood, the play should have either resulted in a touchdown or a clock stoppage giving the Seahawks more chances to run the ball. Because of the outcome, football fans perceive the play call as an atrocious one.

These anecdotes highlight a cognitive bias known as outcome bias. This has to do with one of the most fundamental and underappreciated concepts in sporting events, gambling and investing: process versus outcome (or skill versus luck). Just like the gambler in the hit-on-17 story, investors tend to make similar errors by placing too much weight on the outcome of a decision rather than the process by which the decision was made. The focus on the outcome is to some degree understandable because the outcome is what ultimately matters. However, it could be due to pure luck or some other random factors. People are not good at understanding the interplay between luck and skill. Luck is the force that brings good fortune by chance and not as a result of effort or ability. Skill, on the other hand, is the ability to do something competently due to learned power or acquired knowledge.

Some activities involve more luck than skill (e.g. playing roulette versus investing). There is, in fact, a simple way of determining whether an activity is based on skill proposed by Wall Street investment strategist, author, and professor Michael Mauboussin – just ask if the player can lose on purpose. If they can, it is a skill-based game (to a degree). If they cannot, luck plays a major role (again, to a degree).

A process is simply a methodology utilized to achieve a goal. It could be a simple checklist, or it could be a more sophisticated approach. Processes concentrate on the specific actions that must be followed in a discipled and systematic way, regardless of results. In investing, a traditional process might involve analyzing the last five years of financial statements for a company before buying their stock. Alternatively, more quantitatively oriented investors might develop intricate models with pre-defined rules to decide which stocks to buy and sell.

But investors often are mistaken by associating good outcomes with skill. Often, outsized gains are the result of a lucky stretch for a particular style of investing with the eventuality of that luck running out. Over time, abnormal returns are bound to revert to the mean, or average, as dictated by the law of large numbers. On the other hand, the best long-term money managers all emphasize a systematic and informed process. They are not concerned with failure in the short run due to factors outside of their control (e.g. global pandemic; shifting market sentiment; sudden outbreak of geopolitical events; etc.)

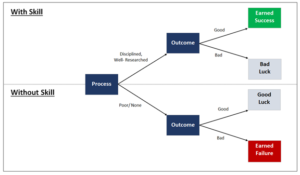

Jay Russo and Paul Schoemaker emphasize the importance of this process-versus-outcome decision making in their book Winning Decisions: Getting It Right the First Time (see Graph below). Their main point is that an individual who relies on process-based decision making deserves praise regardless of the outcome. Likewise, a person who uses a poor process but is met with a good outcome deserves neither praise nor promotion. This fortunate individual is simply the recipient of dumb luck. This is why it is so essential that investors shun activities such as chasing hot stocks or mutual funds that would make them vulnerable to the influence of psychological biases such as herding behavior or short-term oriented speculative trading. Instead, they should follow a more process-driven system to make informed decisions with a long-term perspective. As the co-founder and CEO of Twitter Jack Dorsey has opined, success is never accidental.