The United States entered into a technical recession with the second quarter showing negative growth in real GDP for two consecutive quarters. However, the word “technical” is key. Official recessions are declared by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which takes a more nuanced perspective. The NBER defines a recession as involving “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” The NBER declares recessions retroactively, meaning that they wait for the data to support their conclusions and then determine whether the U.S. has been in a recession. Economic growth is only one component of a recession; the other major factor is much more relevant and visible to most people: the unemployment rate. Fortunately, unemployment is still low and provides no hint that the U.S. is currently in a recession. This, of course, does not say anything about the future direction of the economy. Unemployment is a lagging indicator (that is, it provides an indication of the previous economic state rather than a prediction of the future state). However, robust employment does indicate that the economy is still relatively healthy despite weak consumer sentiment and strong inflationary pressures.

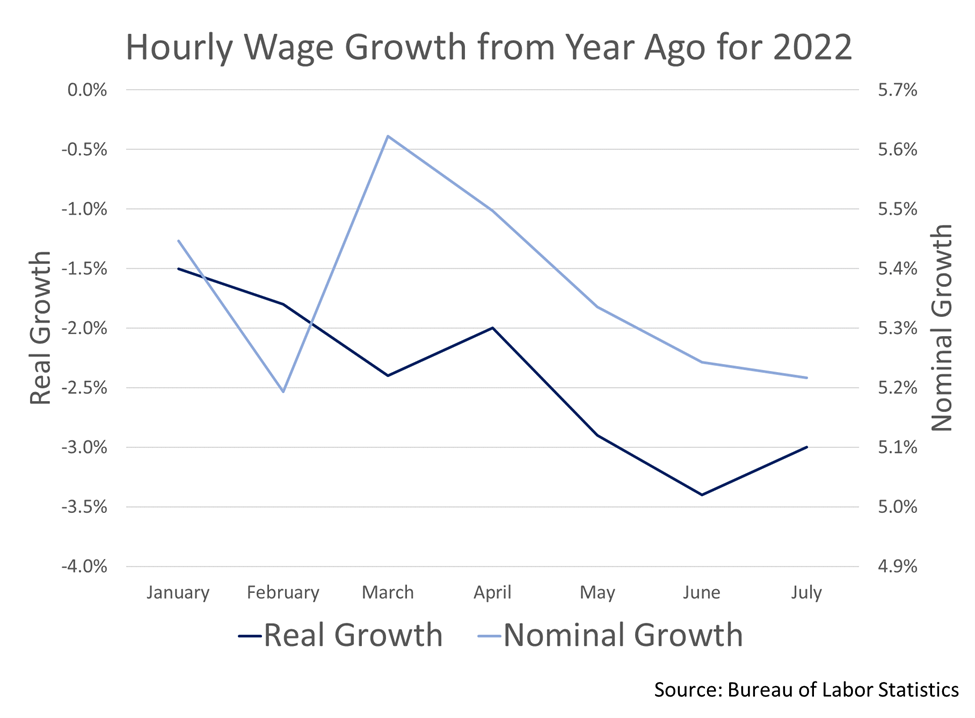

Although many employers are having trouble finding workers, it is debatable whether the U.S. is in a wage-price spiral. This occurs when rising consumption costs spur workers to demand higher wages resulting in a stagflationary feedback loop. There is no doubt that both inflation and nominal wages are rising, but they are not rising at the same rate. While average hourly wages grew by 5.2% year-over-year in July on a nominal basis, real average hourly wages declined by 3% according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This does not imply that a tight labor market and rising wages are irrelevant to inflation, but it does imply that there are other drivers making a greater impact on inflation; primarily supply-chain struggles and energy prices. In July, energy expenditures made up about 9% of CPI, with energy prices rising 32.9% from a year prior. The good news is that energy prices have started to decline over the short-term. Gasoline prices, for example, declined 7.7% from June to July. This led to a welcome slowdown in inflation with prices up in July only 8.5% year-over-year as compared to 9.1% for June. It will take more than one month to reign-in inflation, however, especially as core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy costs, barely budged in July compared to a month prior (albeit after declining more quickly from March to June than the all items CPI). The Fed will likely have to continue being aggressive in order to maintain credibility in its ability and willingness to fight inflation.

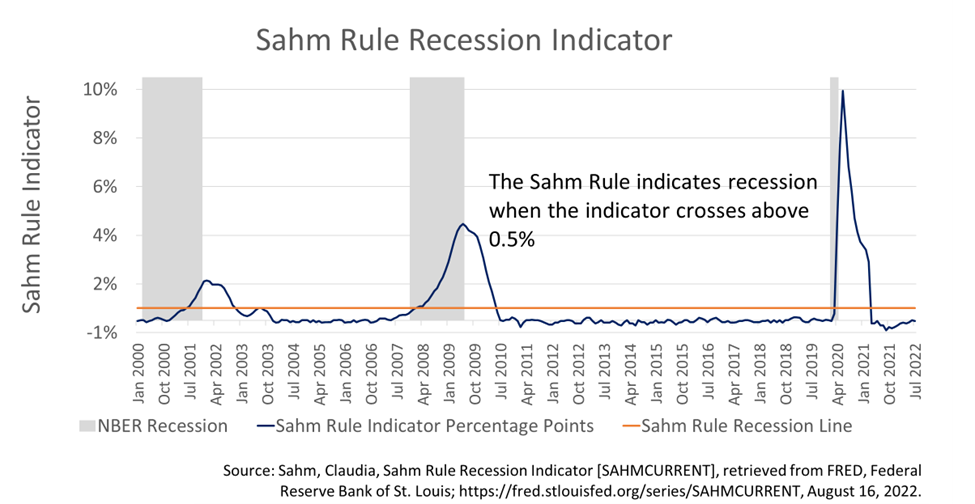

The tight labor market gives the Fed some room to maneuver and still maintain the hope of a soft landing, at least for now. Focusing all attention on the labor market would indicate that the U.S. is not even close to a recession at the moment. One relevant indicator to examine is the Sahm Rule, created by economist Claudia Sahm, which signals a recession as soon as the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate rises by 0.5% relative to its 12-month low. This is meant to be a real-time signal of recession rather than a retroactive declaration, as with the NBER. As one would expect, this is currently well below the 0.5% threshold that would signal recession.

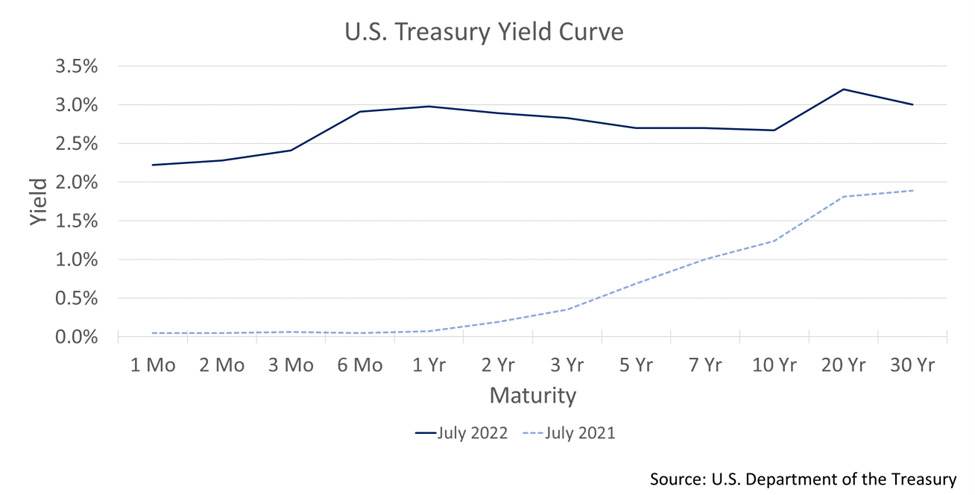

As previously mentioned, unemployment is a lagging indicator, and does not give a strong signal about the future health of the economy. To try to predict future economic conditions, one may do better to focus on leading indicators. One of the best leading indicators is the stock market. This is unfortunate for investors who may try to use recessions as a trading signal. Often by the time the economy is in a recession, much of the damage in stocks has already been done. The S&P 500 Index entered bear market territory earlier this year but has recovered some of the loss. Whether the market is in a true recovery or “bear market rally” remains to be seen, but the heightened volatility does suggest that some investors are wary of an economic downturn. Further evidence of recession fears comes from the U.S. Treasury yield curve. This classic recession indicator is said to forebode recession when it is inverted, or long-term Treasury yields fall below short-term yields as investors price in the anticipation of rate hikes from the Fed (short-term rates are more sensitive to changes in the Federal Funds Rate than long-term rates are[1]). The yield curve is in the process of flattening and has already inverted when comparing the long-term 10-year yield vs. the short-term 2-year yield. Some argue that a better indicator is the spread between the 10-year and 3-month yield, which has not yet inverted, but has been on the verge of inversion since late July. There are other leading indicators as well, which are often combined together into a single index to provide a better signal; but, of course, none of these indicators are perfect predictors.

There is still work to do before the Fed turns dovish again, and investors should not expect a technical recession by way of declining GDP growth to turn the Fed’s attention away from inflation. Many blame the Fed, at least partially, for high inflation due to the vast amount of monetary stimulus injected into the economy in response to the covid-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the Fed made clear that their priority was very understandably lowering unemployment. As the pandemic dragged on into 2021 and unemployment began to fall while inflation started to creep up, the Fed still was focused on unemployment while dismissing inflation as transitory. Then, inflation started to dominate the headlines and the Fed switched gears into inflation-fighting mode. The Fed has been somewhat fortunate in that it has been able to focus most of its energies at one time on either unemployment or inflation; not both. Although the Fed must bring inflation down, Jerome Powell and company must be careful not to lose total sight of the labor market. As rates continue to rise, the Fed’s already difficult task could become more difficult. The Fed will have to walk a tightrope: a wrong step in one direction and inflation will continue to entrench itself in the economy; a wrong step in the other, and workers could begin to lose jobs at a higher rate. If the latter happens, the U.S. could experience a real recession. But that has not happened yet, and there is still a possibility that the Fed can walk the tightrope to the other side without stumbling.

[1] Note that this refers specifically to yields rather than prices. Bond prices are more sensitive to interest rate changes at the long end of the curve.

The views expressed represent the opinion of Passage Global Capital Management, LLC. The views are subject to change and are not intended as a forecast or guarantee of future results. This material is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute as investment advice and is not intended as an endorsement of any specific investment. Stated information is derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources that have not been independently verified for accuracy or completeness. While Passage Global Capital Management, LLC believes the information to be accurate and reliable, we do not claim or have responsibility for its completeness, accuracy, or reliability. Statements of future expectations, estimates, projections, and other forward-looking statements are based on available information and Passage Global Capital Management, LLC’s views as of the time of these statements. Accordingly, such statements are inherently speculative as they are based on assumption that may involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Actual results, performance or events may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements.